To the Editors of the New York Review of Books

Regarding Richard Holmes article, “The Greatness of William Blake” (NYROB, December 3rd, 2015)

Dear Sirs,

I’m an admirer of Richard Holmes’ writings. His biographies of Coleridge I keep close on my book shelf. So I turned to his essay, “The Greatness of William Blake”, with anticipation. I was rewarded with pleasures. He writes a rich Pater-ish prose. I’ve always been impressed with his keen sympathy for his subjects. But I was startled, when, after his summary of the ideas in Heather Jackson’s Those Who Write for Immortality, towards the end of his essay, he joins Northrop Frye with a list of American writers. I may have misread his meaning, but he implies that Frye is part of an American discourse. Frye was born in Quebec; he grew up in New Brunswick, and then spent the greater part of his teaching life at the University of Toronto. All of his major works were written in Toronto.

Holmes rightly says there are many Blakes. And there is a Canadian Blake. The Canadian cunning sublime tacitly diverges from the American imaginative vision and critical debate. So we must diverge, lest we be overwhelmed by the cultural force of the Empire to the south. Frye reinvented Blake in his masterwork, Fearful Symmetry (1947), turning him into a dissident of the imagination, envisioning alternative states of consciousness, heightened states of being, malleable realities, a politics steeped in the missionary imperative to restore visions of a utopian Jerusalem, an exaltation of a singular, prophetic voice calling from the wilderness or the margins.

You find another example of Frye’s radical Blake-like statements in The Educated Imagination (1962). There he heretically (and beguilingly) says that the imagination prevails over ideology: imagination is the source not only of reverie but of transformation. Frye championed seeing realities, not just one reality, on the material plane. His posthumously published essay, The Double Vision (1991, the title drawn from one of Blake’s letters), carries this myriad-minded vision to its extreme: death becomes a mental category, all dimensions of reality subject to poetics. Frye’s insights burned from the intense inwardness of the life he found in Toronto, and from his recognition of the frontiers of the new, northern experience.

His eminent colleague in the English Department at the University of Toronto was Marshall McLuhan. The various McLuhan often turned Blakean, identifying changes of cognition with changes in media (we become what we behold). Blake’s spectacular engravings and visual illuminations influenced McLuhan’s multi-media works, especially The Medium is the Massage (1968) and the aphorisms and advertisements of Culture is our Business (1970). McLuhan’s teasing satiric and revelatory impulses were indebted to The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. If there’s anyone we can claim to be prophetic—uncannily so—it’s McLuhan, who foresaw electronic technology changing how we communicate, what we sense and intuit, even consciousness itself. The global village vision came from a thinker living in a city that wasn’t then the centre of anything.

You can see Blake’s influence through the impact of these formidable teachers (Frye and McLuhan directly and indirectly educated generations of writers, teachers, film-makers, musicians, and politicians) and in many searching Canadian figures. Look at Margaret Atwood’s parables of catastrophe; Irving Layton’s apocalyptic reimagining of the poetics of identity; Leonard Cohen’s phantasmagoric Beautiful Losers (1966), and his beautiful early lyrics of innocence and experience; A. F. Moritz’s elegiac poems where dreamlife and perceptions of mortality fuse; in Michael Ondaatje’s first fictions that spiritedly mix modes. Anne Carson seems to stand aside from the Blakean current in Canada by making Sappho, Euripides, Simone Weil, Emily Bronte, her imaginative companions and collaborators. Yet in Carson’s unique writings there are muted tinges of Blakean ecstasies: her books combine poetry, prose, dramas, images, aphorisms and essays.

I doubt if the redoubtable Holmes would have said that the great Mexican poet, Octavio Paz (himself in Blake’s thrall) was inside the American discourse. You could say Paz is, like Canadian artists and thinkers, part of the Americas. Still, there is this persistence in melding Canadian writers with the Emerson, Whitman, tradition and with contemporary theorists in the United States. This forgets one of Blake’s great auguries: the visionary imagination–charged with paradoxes—is audaciously unique to a time and place, and without borders, a mental realm that gives shape to a communion of inspirations and perceptions. The poetic spirit, unlike Wilde’s muses, doesn’t care for geography (or history) and yet does care.

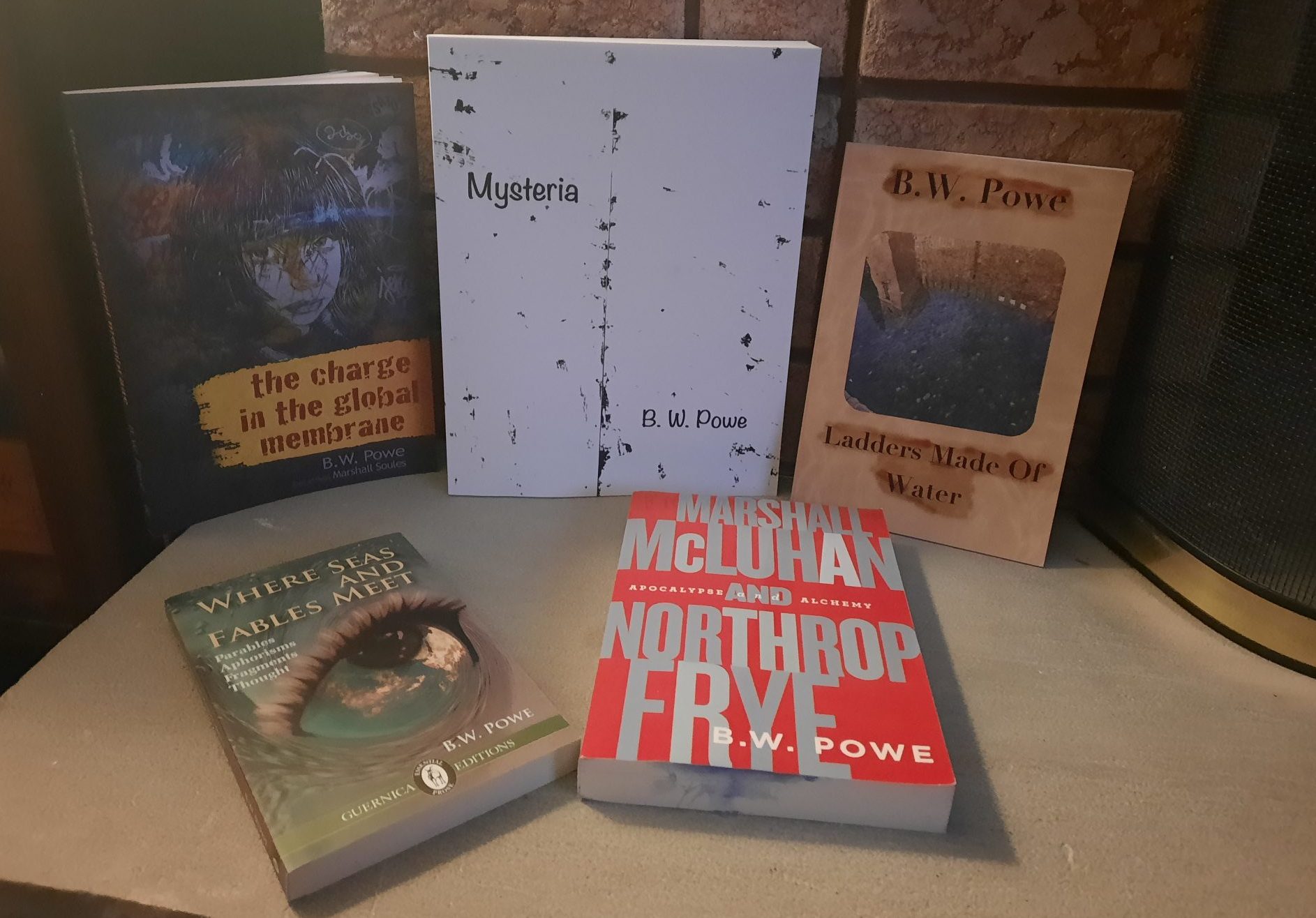

B.W. Powe